The Manly Love of Comrades

by Alexander Schneider

Writer and editor at Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) @homocommunist @aleksandrschneidr

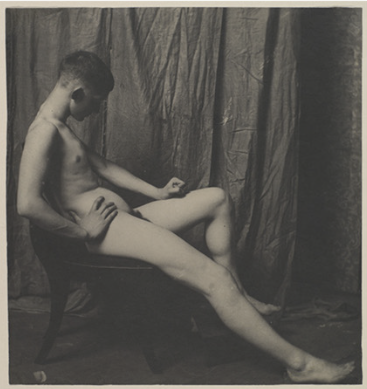

Photographs by Thomas Eakins

Article

Related Articles

Redlist #5

Come, I will make the continent indissoluble,

I will make the most splendid race the sun ever shone upon,

I will make divine magnetic lands,

With the love of comrades,

With the life-long love of comrades.

I will plant companionship thick as trees along all the rivers of America, and

along the shores of the great lakes, and all over the prairies,

I will make inseparable cities with their arms about each other's necks

By the love of comrades,

By the manly love of comrades

—Walt Whitman, "For You O Democracy"

Walt Whitman brought a queer gaze to American poetry with his “Calamus” collection of poems, first published in the 1860 edition of Leaves of Grass, in which poems like “For You O Democracy” describe a sort of fraternal utopia inhabited by “comrades” and fuelled by a undercurrent of homoerotic egalitarianism. In these poems, the titular calamus plant registers as symbol of this homoeroticism, named as it is after Calamus, the mythological youth who, after competing in a swimming contest against his male lover Carpus, allows himself to drown in grief when he realizes Carpus has; both Calamus and Carpus, in their return to the earth, become immortalized as plants. Whitman’s label of “Calamus” thus signals not just same-sex desire, but a desire characterized by youthful vitality, athleticism, and a communion with nature: one that is, above all, embodied. This physicality—connecting bodies, and connecting bodies with nature—becomes the essence of Whitman’s comrade-lovers, the subjects who practice his “manly love of comrades” and populate his vision of brotherhood.

Despite ever-shifting levels of acceptance for his own homoerotic desire throughout his life (“I contradict myself. I am large, I contain multitudes” would become his most famous credo, after all), Whitman himself embodied these desires and put them into practice. He wrote of the “midnight orgies of young men” he would partake in and kept in his notebooks detailed records of the men he encountered or picked up:

Peter — large, strong-boned young fellow, driver. . . . I liked his refreshing wickedness, as it would be called by the orthodox.

George Fitch — Yankee boy — Driver . . . Good looking, tall, curly haired, black-eyed fellow

Saturday night Mike Ellis — wandering at the corner of Lexington av. & 32d st. — took him home to 150 37th street, — 4th story back room — bitter cold night

Wm Culver, boy in bath, aged 18

Whitman’s constant stream of sexual partners—bus drivers, sailors, laborers, soldiers—were all young and all working class. Alongside these prosaic accounts of them, his poetry renders these young male bodies in a more flowery but no less physical manner, as in “We Two Boys Clinging”:

We two boys togherr clinging

One the other never leavign,

Up and down the roads going - North and South excursions making,

Power enjoying - elbows stretching - fingers clutching each other.

Whitman’s vision of democracy and undying, “never leaving” camaraderie becomes inextricable from his reverence for the male body, enough to lead one critic at the New York Herald to denounce the poet’s “disgusting Priapism.” Similarly outrageous, thanks to an equally strong love of the male body, was Whitman’s contemporary, the artist Thomas Eakins. According to Eakins, a naked woman was “the most beautiful thing there is—except a naked man.” Throughout his career, he scandalized American artistic society not only with his paintings of working class young men in little to no clothing, but also by allowing male models to pose nude for his female students. This is not to mention his pastime of going skinny dipping with his male students during outings where during which they would also pose nude for photographs.

Some of these swims became immortalized in Eakins’s artwork, perhaps most famously in The Swimming Hole (1885), in which six nude men, including a self-portrait of Eakins himself, bathe, dive, and lounge, their limbs loosely arranged in a constellation of affinity. These male bodies are embedded in a lush, pastoral setting, the homoerotic subtext of the gentle, vulnerable scene unmistakable. Eakins’s photographic studies that contributed to paintings like this further extend this vision of male camaraderie, and his extensive use of male nudes in anatomical and athletic poses, captured with an almost devotional stillness, put forth the male body as a site of beauty and erotic potential, rather than pure strength.

Other paintings by Eakins, like Wrestlers (1899), which depicts two young, slender athletes grappling under gentle lighting, also seem to propose a softer version of masculinity and kinship; though the two figures are pinning each other to the ground, there is a marked lack of aggression. Eakins submitted Wrestlers as his diploma painting when he joined the National Academy of Design, and was obviously at odds with the sensibilities of some of the more polite subjects on view, in part because of its mundane nudity and because the athletes themselves were, going by their suntanned necks and hands, working class young men.

Given their shared vision of male homosociality embodied in nature, it is no surprise that Eakins and Whitman became each other’s friends and admirers. Indeed, Eakins not only painted Whitman’s portrait, but photographed the poet numerous times, including in a series of full-frontal nudes. Whitman’s poetry seems to prefigure scenes of Eakins’s art (“Twenty-eight young men bathe by the shore, Twenty-eight young men and all so friendly”); Eakins, meanwhile, carried these visions forth into a visual medium that shared the poet’s intense interest in the male form and romanticized masculinity rooted in outdoor life and embodied in groups and pairs of comrade-lovers.

Across the Atlantic, another of Whitman’s admirers (not to mention sexual partners), the British socialist Edward Carpenter, would extend the poet’s vision of homoerotic democracy into a true political practice. Carpenter was so moved by Walt's “manly love of comrades” that reading Leaves of Grass in 1868 would be the spark that would make him leave his comfortable life at Cambridge and dedicate his life and inheritance to socialism and homosexual liberation, becoming a premiere spokesperson for both causes in the U.K., as well as to women's emancipation, anti-colonialism, animal rights, labor unions, and other radical causes. In 1874 he wrote to Whitman: “Because you have given me a ground for the love of men I thank you continually in my heart ... For you have made men to be not ashamed of the noblest instinct of their nature. Women are beautiful; but to some, there is that which passes the love of women.”

Like Whitman, Carpenter located an inherent egalitarianism in homosexual relationships, with comrades-in-arms bridging the gap between classes. Among Carpenter’s writings are several pamphlets about sexuality, including Homogenic Love (1894) and The Intermediate Sex (1908), which argues the rise of “Uranians” might form the vanguard of a sexually liberated socialist society, free from economic and gender subordination: “Eros is a great leveller. Perhaps the true Democracy rests, more firmly than anywhere else, on a sentiment which easily passes the bounds of class and caste, and unites in the closest affection the most estranged ranks of society.” This found expression in his personal life. “My ideal of love is a powerful, strongly built man, preferably of the working class,” he wrote, and his dedicated relationship with George Merrill, a much younger man who grew up in poverty, would eventually inspire E.M. Forster to write Maurice after Forster visited the pair in their cottage, Millthorpe, a rural hideaway where the animal and nature-loving Carpenter would put into practice the sexual politics enumerated by Whitman and aestheticized by Eakins.

The confines of Victorian and Edwardian American and British society would eventually encroach on the broad-minded, shared vision of Whitman, Carpenter, and Eakins. World War I came as a catastrophe for Carpenter, who presumed the Russian Revolution would become the start of a new era of emancipation for Britain and Europe. Eakins was forced to resign from his position at the Philadelphia Academy of Art. Whitman, branded as obscene, was fired from a civil service job in the American State Department, his book nearly banned and rarely republished in his lifetime. The trial of Oscar Wilde, meanwhile, continued to hang over them all. Their aesthetic-political project, fuelled by a “manly love of comrades,” did not ultimately prove enough to dismantle the sexual and political codes of their day, but the archetype of the comrade-lover—physically embodied, bonded across classes, and inextricable from nature—remains a powerful vision today.